Text for Helen’s Dress - an innovative digital visual hospitality program / e-Residency designed by Loukia Richards and Christoph Ziegler, 22-27 June 2020, Vamvakou - Lakonia, Greece

It’s in the air we breathe, in the water we drink, in our language, in everyday life, in every relationship we have, in every science, poem, thought. It’s a veil hard to get rid of. Patriarchy is so deeply anchored in our flesh that it hurts to notice, that we cannot get rid of it all at once. It's not a patch that sticks to our skin, it's the skin itself. We shed our skin, but it takes time. What do we know about Helen? How do we judge her? What does a normal life, a normal reaction look like for us? What do we know about us? Mind the gap.

This is Austria, the normality in which I grew up, the rules that determined the lives of my mother, my grandmother, and my grandmother's grandmother. Until 1975 by law the man was the head of the family, which meant that when they married, woman not only lost their last name, they also had to follow the husband to his place of residence and follow the measures he has taken. The husband had paternal authority over the children and only the father was authorized to sign passport applications or school contracts for the children. He could make statements on behalf of the woman or sign for her without even having consulted her. Women were completely incapacitated and disenfranchised as wives. How much pressure and romantic illusions did it take to get married? It’s all about love. Until 1979 girls were excluded from the subject of “geometric drawing” in secondary schools, until 1987 boys were excluded from the subject “housekeeping”, the participation in both subjects then was mandatory for both genders. Until 1983 children automatically received the father's citizenship. Until 1989 unmarried mothers were only given guardianship for their child by application; the district administrative authority was automatically the official guardian. Until 1989 the acknowledgement of rape depended on the behavior of the victim and was only legally recognized when the woman defended herself until she unable to resist. Would you put your life at risk? And until 1989 rape was not possible in marriages or extra-marital cohabitations, because the man had a right to have sex with “his” wife and the woman had no right to refuse. How can you say no to love? Defending her “no,” and herself in this case was an attack. Love always wins. Until 1993 in schools the subject “textile work” was only for girls, and “technical work” only for boys. Since 2006 there is a law against stalking, and only since 2016 men have to accept that “no means no.”

I'm only talking about a few, almost randomly selected facts, there is so much more. That has been our normality. That was the framework on which every interpretation of texts and artifacts was based, and still is. But even the list of facts appears to some as radical feminism, or as exaggerated, know-it-all, hysterical and complicated. For me, this list means that events in my life that I felt to be deeply wrong and injust were at their time actually perfectly legal. Why complain? It all happened out of love.

What does this have to do with Helen's story? There is a massive, millennia-old filter over all our thinking. Her story was told by men, in the interests of men, from the point of view of men. Even where she speaks herself, it is Homer who puts the words in her mouth. Whom do you think he represents? And yet analyzes follow and trust the author's voice. Even an author such as Ruby Blondell, who published widely on gender studies, follows the usual pattern in her interpretations.

“Helen of Troy is the mythical incarnation of an ancient Greek obsession: the control of female sexuality and of women’s sexual power over men. As the most beautiful woman in the world, and the most destructive, she is both the most in need of control and the least controllable. When she escapes male oversight by absconding to Troy with her lover, Paris, she triggers the greatest war of all time: the Trojan War. Though her departure is typically referred to as an “abduction,” none of our sources claims that Paris took Helen by force against her will. Her complicity is essential to her story. Yet the men who set out in hot pursuit share responsibility for the devastation that results. The war is caused not only by their inability to control the beautiful Helen but their equal inability to dismiss or destroy her.”

Seriously? Helen’s power is beauty, and this beauty is evil. And she did not defend herself! No interests beyond love. Whatever she does, it only makes her more guilty of all the destruction. She is silent - guilty. She speaks - guilty. And as she calls herself guilty, she definitely is the bitch to blame. Don’t ever trust a woman, don’t ever give her any rights, don’t ever loose control.

“Helen is acknowledging her own power. She is outing herself as a Pandora, a beautiful woman with an evil interior, who uses her power of agency in ways that cause misery to men.”

Whatever happened, it does not really matter. Women are corrupt and evil from the ground up. Pandora, Eva, Helen, the archetypes of the woman who transcends her natural, divine boundaries, the seductress who destroys men. It is known where the woman's place would be: at home, at the loom, following the instructions of her husband. In the whole argument, I still see the legal framework of the past decades, past millennia. Didn't the Inquisition argue very similarly?

“Helen thus retrojects her own subjectivity into the originary transgression that caused the war, despite the efforts of others to deny it. Her acceptance of responsibility is, in its way, an act of defiance. As such it enables the poet to have his cake and eat it, making Helen a “good” woman and thus worth fighting for, but also blameworthy, presenting her as a precious but passive object of men’s desires, while also allowing her a measure of subjectivity and (retrospective) agency.”

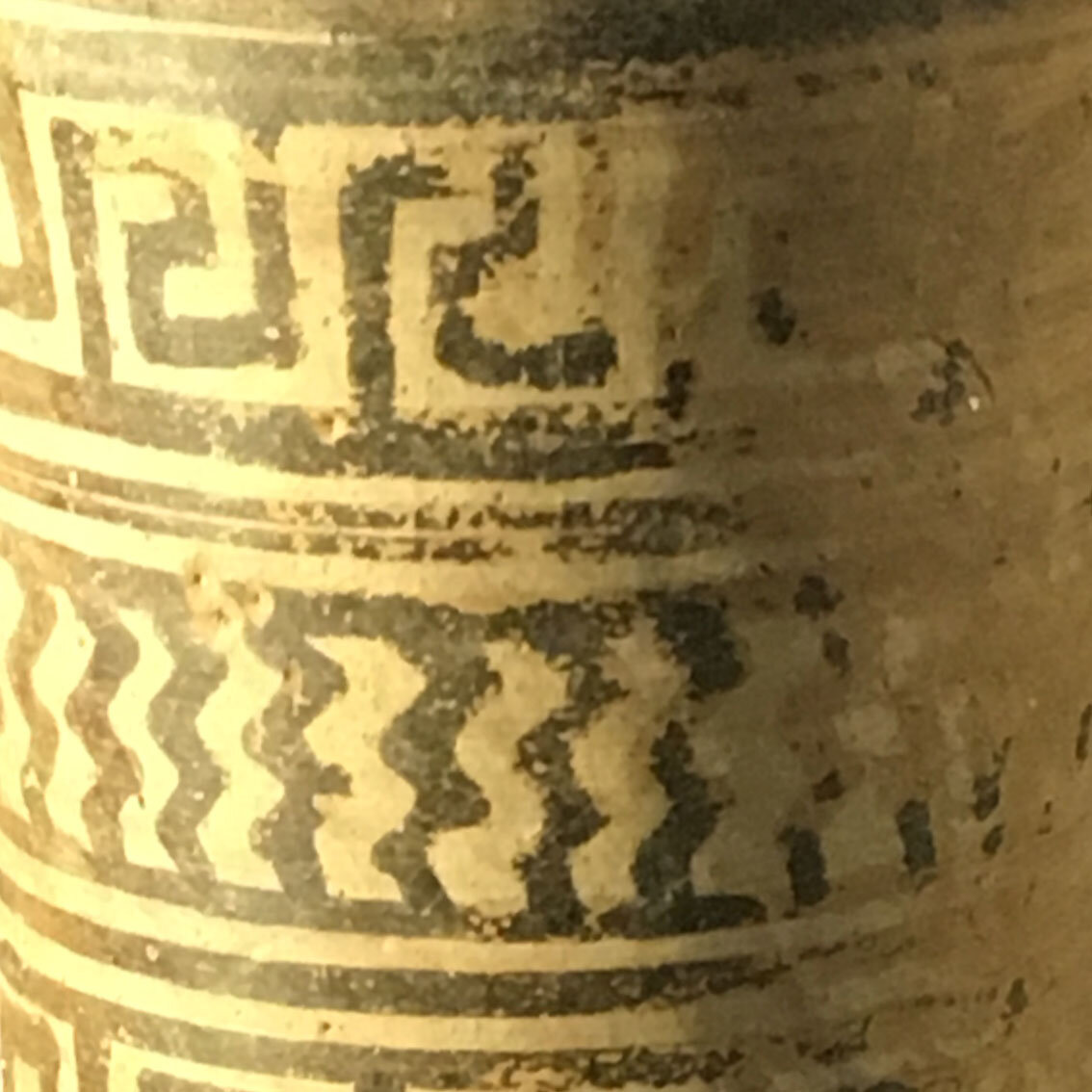

Homer indeed did a good job, so good, that until the present day it is hard to get the simple facts. So I try to follow logic. The heir to the throne was matrilinear, so the husband of Helen, the Queen, became king. Even if Helen leaves Sparta, whether voluntarily or not, she remains queen. If she dies, her daughter becomes queen. But if she marries, her new husband becomes king of Sparta. In this sense, Paris was king of Sparta, not Menelaus. Helen's irresistible beauty was that ability to make men king. Menelaos could not take revenge on her and murder her, because then his rule would have been finally over. This is completely inconceivable from a patriarchal logic, and at a time when a matriarchal social form was still remembered, it was all the more important to find an alternative narrative. Out of a matriarchal logic, Helen was not an adulteress. Only in a patrilineal society do women have to be restricted to sex with a single man to ensure legitimate children.

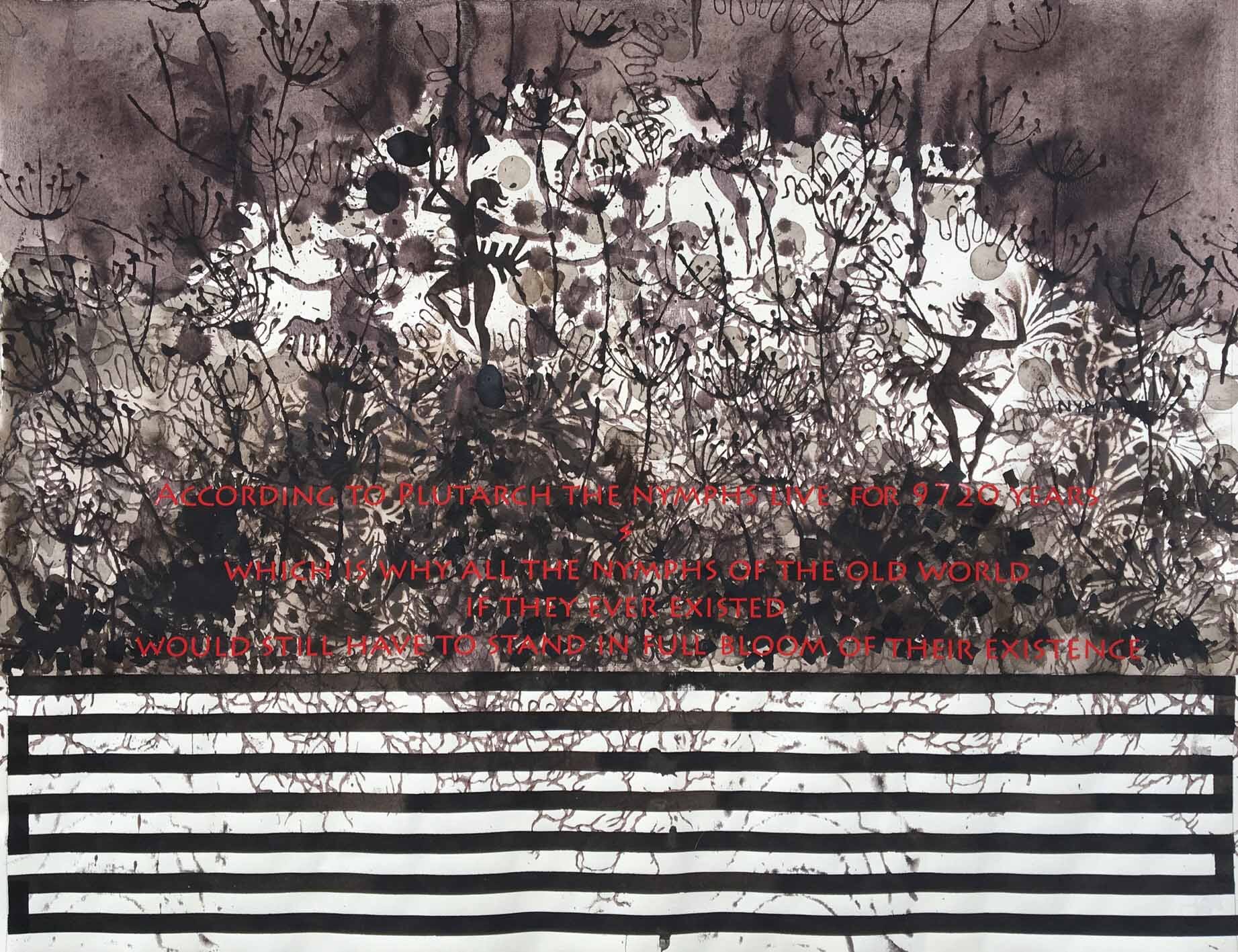

It is time to face the old texts with new questions and experience how differently these stories could be told. It is time for fresh air to breathe, fresh water to drink, a new language, and a different everyday life, different relationships, different science, poems, thoughts. It is time to get rid of the veil of patriarchy.